Who exactly was the real Charlotte “Charley” Parkhurst? And what inspired my novel The Whip based on Charley Parkhurst’s life?

When I was a young woman, I used to read Cosmopolitan magazine–searching the pages on ‘how to find a man!” Instead of that ‘important’ information, one day I found a fascinating article on Wild Woman of the Old West. One of the ‘wild’ women written about was a Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst (1812–1879). She fascinated me. The idea of a woman living her life as a man and not being discovered (with all of those macho stagecoach drivers she hung out with) was amazing to me. I wondered how she could she have carried off her disguise for 30 years and not be found out. I also couldn’t imagine being so isolated from people to keep such a secret. And then there was the big question of why she chose to live as a man, in the first place. As the years went by, I used to think about Charley and what a wonderful book her story might make. One day, I decided to do some research on Parkhurst and found only a sparse amount of information written about her.

In my research, I encountered these biographical facts that we know to be true about Charlotte “Charley’ Darkey Parkhurst:

Born in New England and growing up in an orphanage, Parkhurst ran away as a youth, taking the name ‘Charley’ and living as a male. (a single woman could not travel alone in those days) She started work as a stable hand and learned to handle horses and to drive coaches drawn by multiple teams.

Seeking opportunities in California following the Gold Rush in 1849, Parkhurst, in her late 30s, left Rhode Island, sailing on the R.B. Forbes from Boston to Panama. Travelers had the very difficult journey of crossing the Isthmus overland and if they survived, they had to pick up another ship on the west coast to take them to their destination.

Parkhurst went on to work for James E. Birch of the California Stage Company, where she developed a reputation as one of the finest stagecoach drivers

(“whips”) on the West Coast. Parkhurst’s prowess as a driver inspired her nickname, “Six-Horse Charley.” She was ranked with “Foss, Hank Monk and George Gordon” as one of the top drivers of her time.

Among Parkhurst’s routes in northern California were Stockton to Mariposa, “the great stage route” from San Jose to Oakland, and San Juan to Santa Cruz. Stagecoach drivers carried mail as well as passengers and had to deal with hold-up attempts, bad weather, and perilous, primitive trails. On one occasion, the bandit called “Sugarfoot” (he wrapped burlap sugar sacks around his boots) ordered Charley to ‘throw down the box” (the strong box.) Parkhurst obeyed, but was determined to settle the score. As luck would have it, Sugarfoot stopped her coach again on the same route. This time Charley shot and killed him

Some time after reaching California, Parkhurst lost the use of one eye after a kick from a horse, leading to her nickname of “One Eyed Charley” or “Cockeyed Charley.”

In 1868, Parkhurst was the first known female to vote in a presidential election (though passing as a man). She voted for General Grant. Seeing that railroads were cutting into the stagecoach business, Parkhurst retired from driving some years later, retiring to her ranch in Watsonville, California. For fifteen years she worked at farming and doing lumbering in the winter. Parkhurst later moved into a small cabin about 6 miles from Watsonville and suffered from rheumatism in her later years. She died there on December 18, 1879, due to tongue cancer.

When doctors were getting her ready for her funeral, they were shocked to find out that the great Charley Parkhurst was indeed a woman — who had had a child! A trunk in the house contained a baby’s dress. The discovery of her true gender became a local sensation and was soon carried by national newspapers.

Parkhurst’s obituary from the San Francisco Call was reprinted in The New York Times on January 9th, 1880. The headline was: “Thirty Years in Disguise: A Noted Old Californian Stage-Driver Discovered. After Death. To be a Woman.”

The article noted how unusual it was that Parkhurst could have lived so long with no one discovering her assigned gender, and to “achieve distinction in an occupation above all professions calling for the best physical qualities of nerve, courage, coolness and endurance, and that she should add to them the almost romantic personal bravery that enables one to fight one’s way through the ambush of an enemy…” was seen to be almost beyond believing–but there was ample evidence to prove the case.

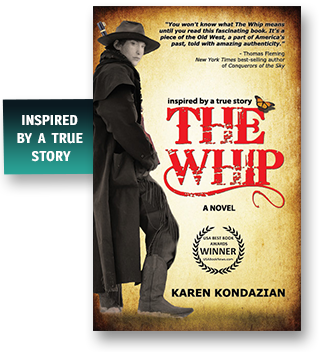

I put Charley’s research aside for some years but In 2005, my mother passed away. I decided I would put ‘pen to paper’ and begin writing The Whip… and dedicate the book to my mama and dad. Six years and twenty-seven drafts later, I finished the book and was fortunate to find the boutique Hansen Publishing Group to take The Whip on.

Throughout the writing process, I would go to Watsonville, California, where Charley is buried in The Old Pioneer Odd Fellows Cemetery. I visited her grave and interviewed a couple of folks whose relatives had known Charley or were somehow connected to her. I then took their stories and ‘rumors’ about her as well as what we know about Charley historically – and fictionalized the rest. On the cover of the book I call it, ‘a novel inspired by a true story.’

Mark Twain said “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth is not.” I suppose Charley Parkhurst’s life verifies Twain’s quote to the hilt.